How Australian businesses can participate in the changing Chinese economy

The opportunities for Australian investors in the past was focused on commodities. Urbanisation, the growth of over 113 cities with a population of over 1 million people and China’s vast infrastructure spending has led to a seemingly unstoppable demand for Australian commodities, especially iron ore.

China’s focus has now pivoted from being a manufacturing powerhouse to taking a more insular approach focusing on the Chinese consumer. This presents a huge opportunity given the size of the Chinese middle class which equates to the entire US population. Although the absolute level of household wealth is low by developed markets standards, it is an enormous market given the size of the population. The size of the middle class (people earning US$10,000-US$40,000 per annum) in China is set to double from ~300m people to over 600m in the next decade. At this level, China will make up close to a third of the global middle-class population.

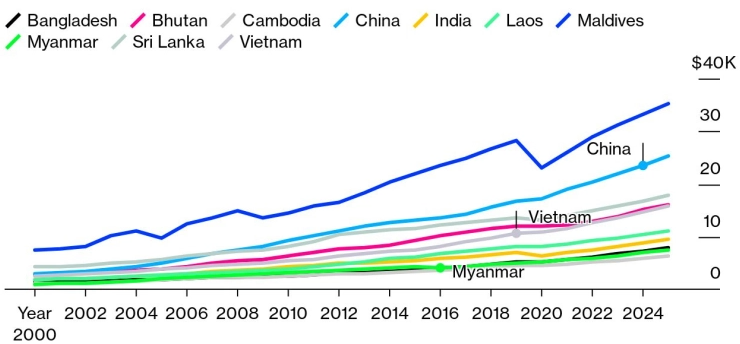

Figure 1: Growth in GDP per capita for selected Asian countries

Source: Bloomberg

As wealth increases, household spending shifts from necessities to discretionary items. Consumers trade up to more expensive brands and spend more on services such as travel and education.

This transition changes the opportunity set for investors. In the past, the likes of TWE and A2 Milk offered investors opportunities to leverage the Chinese growth/rising affluence story. The future opportunity is more nuanced.

China is a complex country in which to do business, with a regulatory environment that is subject to material, unexpected changes and unique consumer tastes which can often be directly influenced by government policy. More recently, a cooler diplomatic relationship between China and Australia has added an extra layer of complexity for Australian companies.

Accessing the Chinese Consumer

There are three ways which businesses typically sell products into China: via the grey market or daigou channel, via cross border e-commerce platforms and via officially regulated channels, i.e. in-country retail. Businesses looking to operate in China must consider the best route to market when formulating their strategy.

- Daigou: the daigou channel is unregulated and can be considered a “grey market”. It has operated in various forms as a route towards selling foreign goods to Chinese consumers for decades. Fundamentally, the daigou market involves the purchase of goods in Australia (or another country), shipping them to China and then reselling them to Chinese consumers. The daigou’s profit is the difference between prices in Australia and China. Daigou can be influential in building a brand for companies in China, as has been the case for A2 Milk. However, daigous can be quick to abandon a brand if their margins are squeezed, as A2, Bellamy’s and Blackmores have discovered. The daigou channel is opaque – there can be five or more layers of distribution – and companies can lose track of inventory, which can cause supply issues. Despite the lure of higher margins due to lower marketing and fulfilment costs, firms tend to avoid overreliance on this route to market given the significant downside risks if a problem arises.

- Cross border e-commerce (CBEC): CBEC is a relatively new channel to market and involves foreign companies selling goods via e-commerce platforms, the most well-known being Alibaba’s Tmall platform. The CBEC channel has experienced strong growth since the establishment of “free trade zones” in 2013 (where products are imported before being delivered to consumers) and the general rise of e-commerce in China. China has some of the highest e-commerce penetration rates in the world and this continues to grow. However, it is difficult for companies to build brands on e-commerce platforms, as the customer relationship is typically with the platform, not the brand. In addition, e-commerce platforms often demand significant rebates for favourable positioning on sites.

- In-country retail: the most official and regulated way to sell goods in China is through an on the ground retail presence. This go-to-market strategy is complicated to establish and often requires the help of a Chinese partner company or distributor. This channel allows a company to get closer to the consumer and build brand equity on the ground in China. Further, employing local workers, paying taxes, and investing in the domestic economy is a more palatable proposition for the Chinese government. However, the cost and complexity of doing business in China can weigh on margins relative to other channels.

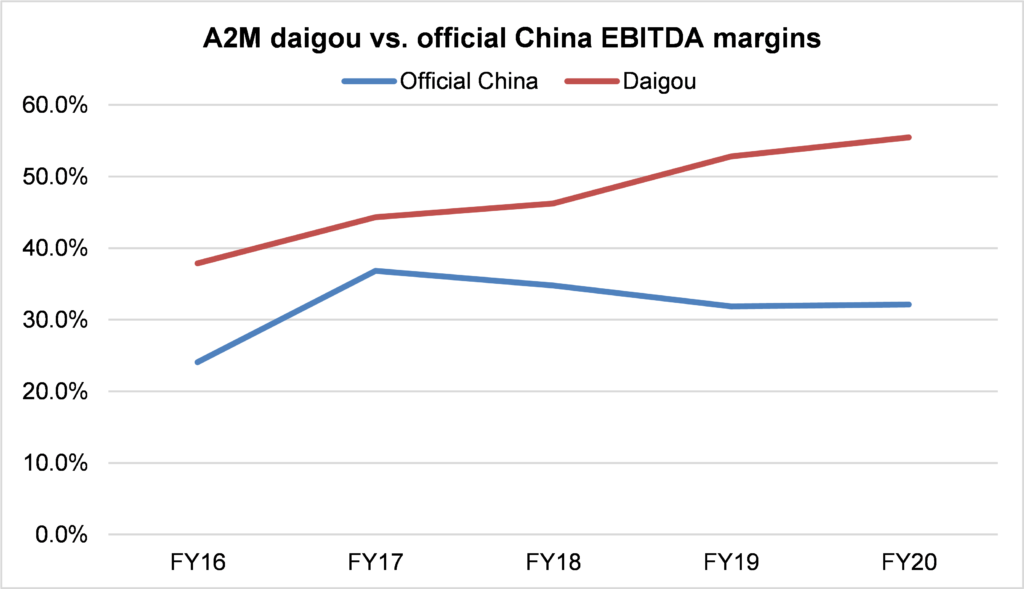

A2 Milk until recently, has been a major beneficiary of rising wealth in China and operates across all three channels. It initially built its infant formula business in the daigou channel before expanding through the CBEC channels and brick and mortar maternity stores in China. A2’s profit margins are considerably higher in the daigou channel, which made it difficult for management to move the business away from this route to market. During COVID, as the flow of people and goods slowed, the pricing spread between Australia and China narrowed and the daigou trade ground to a halt, severely impacting A2 Milk’s revenue and profit margins. In contrast, growth in A2M’s bricks and mortar business has remained strong. A2’s experience over the past 12 months highlights the risks of over reliance on the daigou channel for companies selling into China.

Figure 2: A2 Milk EBITDA margins across different channels

Source: A2 Milk

Exporting or building a business in China

A more sustainable approach involves setting up a wholly owned foreign entity on the ground, keeping as much of the business in China and employing mostly Chinese nationals. This strategy concentrates investment and employment within China, while Chinese employees typically have a better understanding of how to navigate supply chains and appeal to local consumer tastes. Ideally, a business would operate end-to-end in China, contributing to the domestic economy and minimising geopolitical risk.

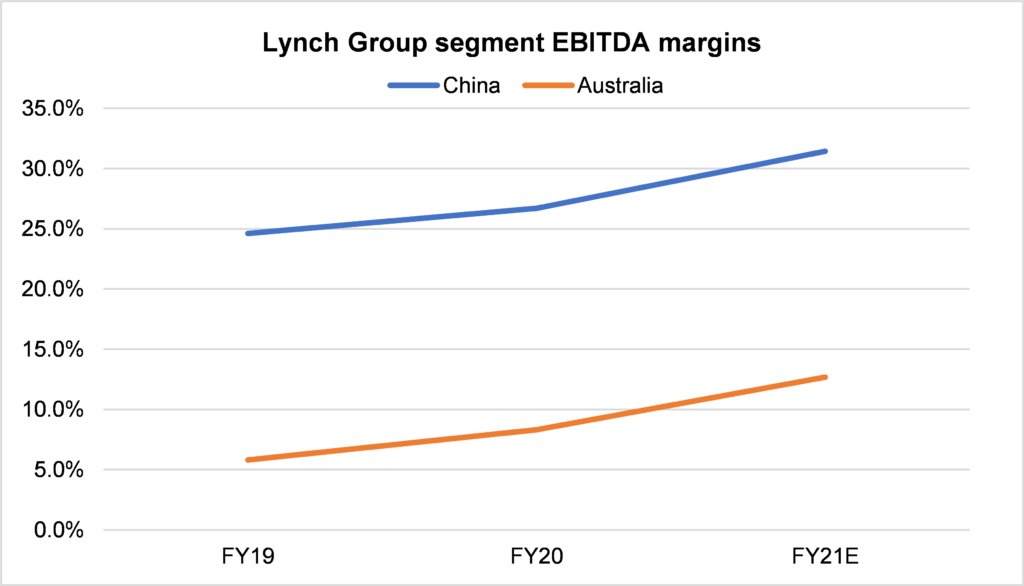

Lynch Group, a vertically integrated flower wholesaler, takes this approach. Although the Chinese market is the fastest growing part of their business, Lynch is not overly reliant on China, with roughly 20% of earnings coming from the country. Given lower farming costs, Lynch’s operating margins in China are more than double its margins in Australia.

Figure 3: Lynch Group China vs. Australia EBITDA margins

Source: Lynch group

Lynch has been operating in China for almost two decades and its entire supply chain operates domestically, from farms in Yunnan province all the way to delivery of product to retailers like Sam’s Club (owned by Walmart), Hema (owned by Alibaba) and Ole (an upmarket grocery chain). The outlook looks positive as the list of retailers offering their product grows. Furthermore, by employing locals and keeping investment within China, Lynch minimises trade and political risks.

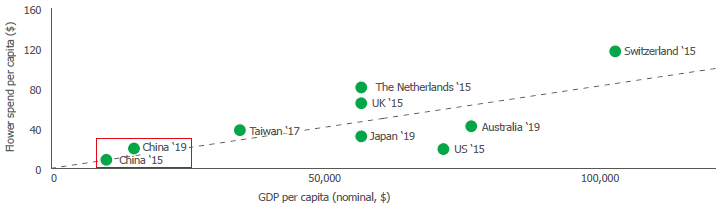

Figure 4: GDP per capita vs. flower spend per capita

Source: International statistics Flowers and Plants 2020

Lynch has leveraged its 100 years of operational expertise in Australia in the Chinese market, allowing it to operate more efficiently than local competitors. Its vertically integrated model means it can supply a superior product to retailers at cheaper prices than smaller competitors. Per capita spend on flowers has a strong correlation with GDP per capita and Lynch has benefitted from increasing affluence, leading to rising daily consumption of flowers in China. Companies such as Lynch Group, who are operating within the parameters set by the Chinese government can thrive. The long-term growth outlook for Lynch in China is positive and, in our view, has been dismissed by the market due to recent China related issues for other ASX listed companies.

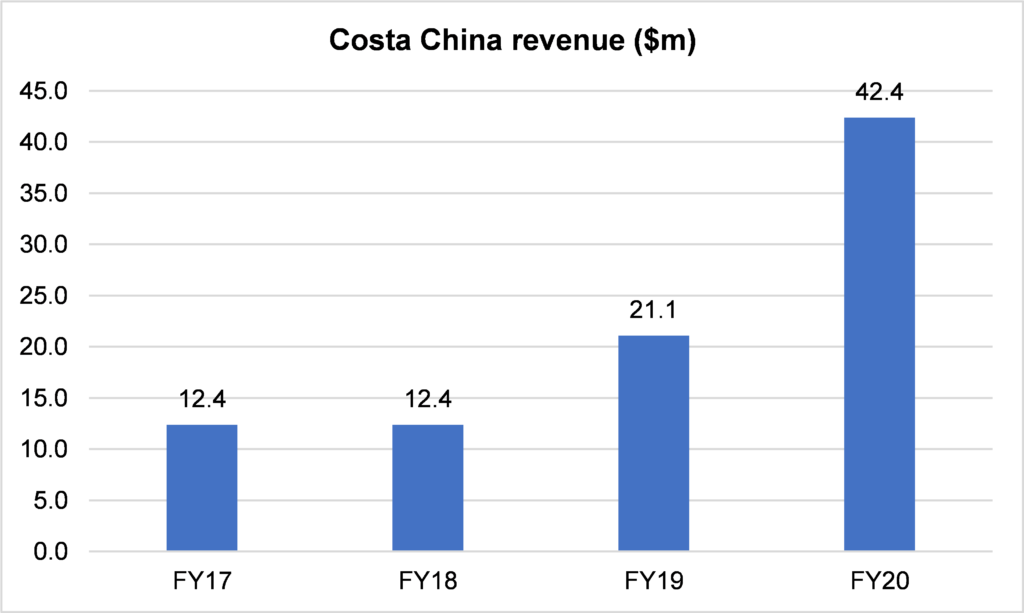

Another example of an ASX-listed company that has employed this strategy is Costa Group (CGC), which has a joint venture in China. Costa operates blueberry farms in Yunnan province, employing local workers and supplying its JV partner, Driscoll’s, which sells and markets the berries to retailers in China. CGC has been operating in China for over a decade and revenue has grown from $12m to $42m in the past 3 years as Chinese consumption of fresh fruit and vegetables has soared. China is set to become the world’s largest blueberry market by 2025.

Figure 5: Costa Group China revenue

Source: Costa Group

A major concern for businesses operating wholly in China is the difficulty in repatriating profits back to Australia. The correct corporate structures need to be set up and profits need to be earned for multiple years before profits can be sent back to a home country. This may give some companies pause when considering setting up a business in China.

Doing business in China is complicated and presents unique challenges. Building a domestic footprint in China takes time and money and has no guarantee of success. While taking this route can ultimately lead to a more sustainable business and insulate companies from geopolitical risks, it carries its own, idiosyncratic risks that need to be managed.

Opportunity for Services

One of the most challenging elements of doing business with China is the regulatory environment. Regulations in China can change meaningfully without warning and are often different for foreign and domestic companies operating in the same industry. We have seen regulation in China impact Australian companies in several ways, including: implementing tariffs on imported goods (wine, lobsters, barley, lobsters, coal), introducing new approvals processes for goods to clear (vitamins and infant formula) or cracking down on marketing programs (casinos). In addition to overt regulation, the Chinese Government has used rhetoric and the media to try and influence consumer behaviour. This may involve promoting or discouraging certain travel destinations or highlighting the quality of domestically produced goods relative to foreign goods.

Services businesses are more insulated from regulatory risks. With less direct control from the Chinese government, decisions are more heavily influenced by consumer choice. It is much more difficult to introduce a tariff on a service than a good. Additionally, as per capita income rises in China, spending is likely to shift from goods to services, which are typically more discretionary purchases.

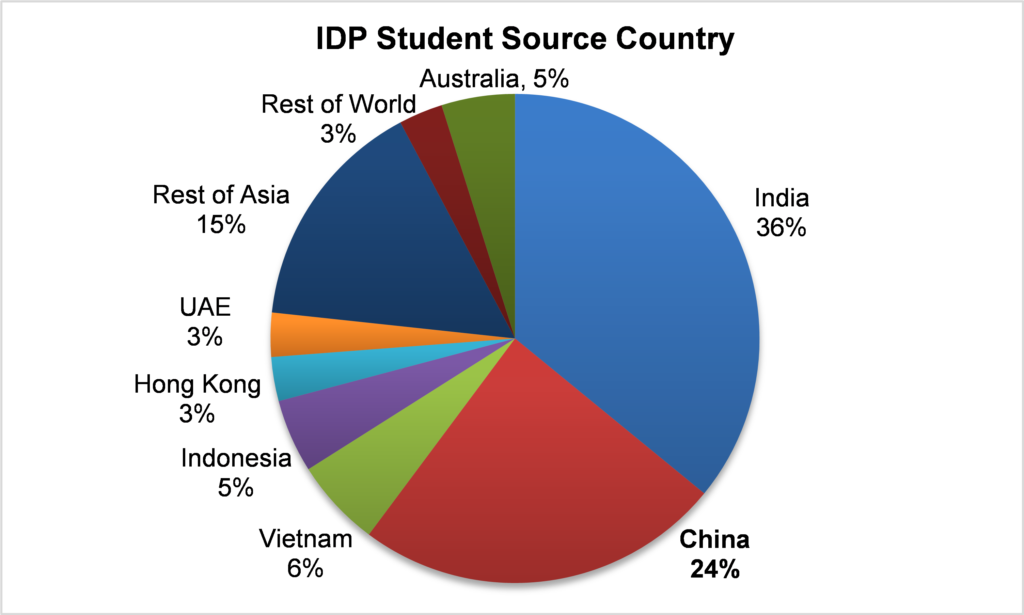

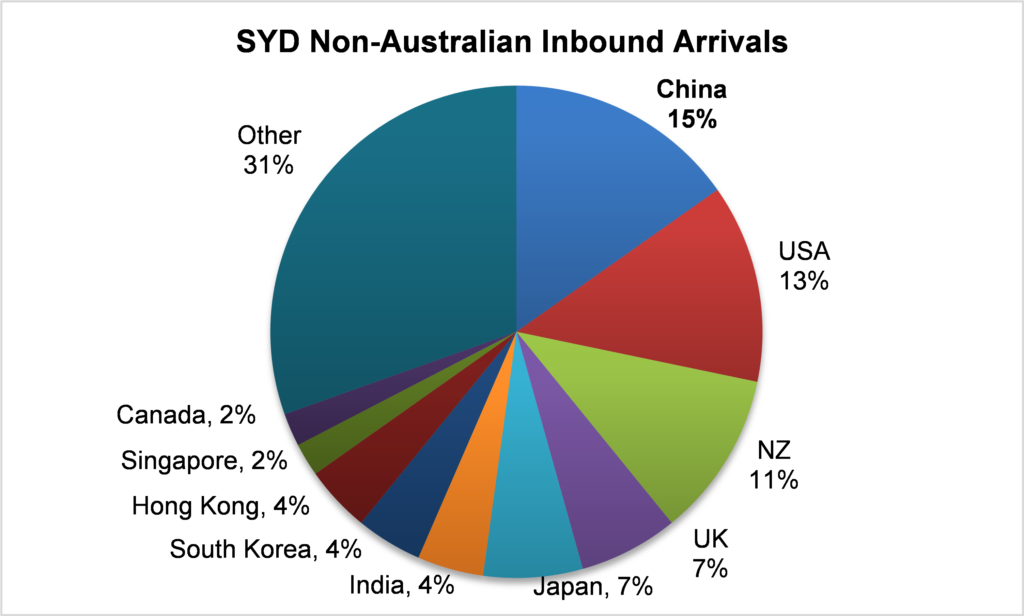

This benefits stocks such as international student placement agent IDP Education (IDP) and Sydney Airport (SYD). China is the largest source of non-Australian inbound arrivals for SYD and the second largest source market for IDP students, having recently been overtaken by India.

Figure 6: Source country of IDP Education students

Source: IDP Education

Figure 7: Source country of Sydney Airport Inbound Arrivals

Source: Sydney Airport

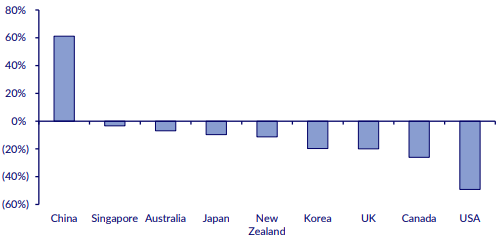

Both IDP and Sydney Airport have been severely impacted by COVID induced travel bans, however, we expect tourism and international education – both from China and elsewhere – to rebound strongly as restrictions ease. We do not expect recent attempts by the Chinese government to discourage students from opting to study in Australia to have a meaningful impact on IDP’s business given its strong presence in multiple study destinations. In addition, surveys of prospective Chinese students suggest Australia is still seen as an attractive place to study, despite government rhetoric.

Figure 8: Change in views of a country’s favourability as a study destination (% of net respondents who said more appealing)

Source: CLSA

Changing consumer preferences

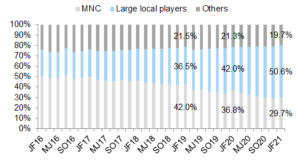

A more recent phenomenon in China is the growing trust in, and preference for, domestically produced goods and brands. For many years, Chinese consumers saw foreign brands as higher quality and a mark of status. This was perhaps most pronounced in the infant formula industry, where distrust of domestically produced formula soared following the melamine scandal of 2008. The retail market share of imported infant formula brands rose to over 50% between 2013 and 2016. Foreign brands have also dominated the luxury goods, cosmetics, sporting goods and electronics industries in recent years, especially at the high end.

However, this has begun to change, with the popularity of domestic brands and goods increasing relative to imported goods, especially among younger consumers. Drivers of this change in attitude toward domestically produced products include the improving quality of Chinese made goods and a heightened sense of nationalism in younger Chinese people.

For example, the market share of imported infant formula has fallen back to ~30% as domestic brands, most notably Feihe, have gained consumer trust and grown strongly. Home grown brands such as Li Ning (sportswear), Florasis (cosmetics) and Xiaomi (electronics) have all prospered in recent years as consumer tastes have evolved.

Figure 9: Retail market share of infant formula in China

Source: Nielsen, Goldman Sachs

The Chinese government has actively encouraged consumers to prefer domestic brands. It introduced the concept of the “dual circulation” economy in its latest five-year plan. A key pillar of this is the focus on domestic production and consumption of goods and services. To take advantage of this dynamic, several companies have recently announced plans to onshore manufacturing and production in China to better service this market. Even infant formula companies such as Danone and Nestle have stated they will establish facilities in China and brands with locally sourced ingredient – a strategy that as recently as two or three years ago would have been considered extremely misguided.

This trend appears to be accelerating and will likely provide a headwind to the many foreign consumer companies globally looking to China to drive growth. Companies can no longer assume that merely being of foreign origin will lead to Chinese consumers placing a quality premium on the product, and instead must find a way to appeal to a more nationalistic consumer. To succeed requires adapting to the changing regulatory environment and evolving consumer preferences.